In a quiet corner of Athens, the Lela Karagiannis” Primary School stands as a bridge between the past and present. Named after the iconic WWII resistance hero, the school is housed in two very different buildings: a neoclassical structure built in 1899 and a newer one constructed after the 1981 earthquake, following updated building codes.

Figure 1. On the left, the newly built wing; on the right, a glimpse of the neoclassical building.

As part of the SIRCULAR Project, which is committed to creating digital tools, technological solutions, and services to drive the decarbonisation and circularity of the built environment, the Hellenic Passive House Institute (HPHI) monitored temperature and humidity in one classroom of each building over three cold February days (12–14 February 2025), when the average outdoor temperature hovered around 10°C.

The results? Telling.

Inside the neoclassical gem, temperatures frequently dropped below 14°C, especially in the mornings. Its thick stone walls retained cold rather than warmth. Humidity levels rose to an average of 54.5% during school hours, creating a damp, uncomfortable environment for students trying to learn. The average indoor temperature during school hours was approximately 15°C.

The newer wing, despite its modern building envelope, didn’t offer the comfort one might expect. The average classroom temperature hovered around 20°C, while humidity ranged from 27% to 48%—an improvement, but still on the edge of thermal comfort. Notably, two different heating systems were operating inside the classrooms (A/C on top of natural gas), highlighting that newer construction alone does not guarantee effective thermal performance. It’s a clear sign that age alone doesn’t define thermal performance, and even newer buildings can underperform without proper insulation, windows, shading, heating, and ventilation strategies.

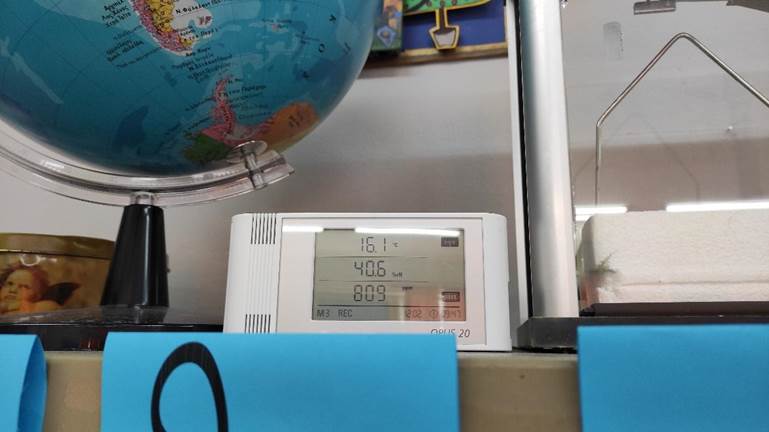

Figure 2. Monitoring device in a classroom showing an internal temperature of 16.1°C.

In Athens—and across Europe—there are questions we must answer before hasty interventions are made. Thanks to detailed monitoring and analysis, the path toward sustainable, student-friendly learning environments is becoming clearer—one graph at a time.

The takeaway? Preserving history is vital—but so is ensuring every learner can thrive in a space that’s not too cold, not too dry, and just right for growing minds.

Τhe solution: Passivhaus EnerPHit Certification

A certified Passivhaus offers constant temperature between 20-25°C, 35-55% Relative Humidity, and CO2 concentration below 1000ppm. These interior conditions offer the students and teachers the best possible indoor environment while consuming the minimum energy for heating and cooling (below 15kWh/m2 yearly). At the same time, NTUA and HPHI are designing a circular prefabricated renovation system including insulation, windows, airtightness and mechanical ventilation with heat recovery to examine possible solutions. Prefabrication in renovation will accelerate buildings renovation, improving time and quality and minimizing errors.

City of Trikala: A case study

The city of Trikala already has two cases similar to SIRCULAR’s virtual pilot:

a. A renovated Passivhaus Heritage Building

Figure 3. Passivhaus heritage museum building at Varousi, Trikala

b. A Passivhaus Primary school

Figure 4. Passivhaus primary school in Trikala.

As part of the SIRCULAR project, HPHI is currently developing a documentary about the renovated primary school in Trikala. HPHI will enclose research and lessons learned from the city of Trikala and the students/users living experience.

Author: Mariza Gkadri, Hellenic Passive House Institute